Iconic refrigeration frozen in time

1st March 2014The Cooling Post has uncovered a huge amount of new information, photographs and drawings of the historic Grimsby Ice Factory, enough to begin a new three-part feature on the history of the Grimsby Ice Factory and the unique refrigeration equipment it contains.

In this first part, we take a general look at the history of the Ice Factory and its refrigeration systems. In part 2 we will explore in more detail the workings of the 1930s J&E Hall equipment, much of which still remains within the building, and then, in Part 3, delve further back to information that has been unearthed on the first and original refrigeration system that has long since been lost to history.

Austere, forbidding, yet forlorn, it crouches on a virtually flattened dockside with nothing to protect it against the east winds that now whistle through its rapidly decaying structure.

Once it was the largest factory of its kind in the world, supplying ice to one of the busiest fishing fleets in the largest fishing port in the world. Now boarded up and derelict for more than 20 years, the preservation of the Grimsby Ice Factory is the subject of a campaign by a determined group of locals, keen to save it and transform it into a major regional arts and leisure facility.

At first sight it’s countenance might suggest otherwise but it has been described as one of the world’s most treasured places. And it’s Grade ll* listed by English Heritage, but not so much for the building as the unique and historic refrigeration equipment still within the building. And it is this equipment which will have to be incorporated within any plans for its future use, providing a lasting reminder of a golden age of refrigeration.

The most significant pieces of equipment are four huge 80-year-old J&E Hall ammonia compressors, and another of a similar size installed in the 1950s. They cannot be removed without demolishing the building, and have stood silent like sentinels, waiting on others to decide their fate ever since the factory finally closed its doors in 1990.

It is these compressors, at the heart of what was the largest refrigeration installation of its time, that form the major part of this article, but first it is interesting to go back to the beginning.

Opening

The Grimsby Ice Factory was built on the dockside and opened on October 9, 1901, as a joint initiative between the Grimsby Ice Company and the Grimsby Co-operative Ice Company. It was not the first ice factory in the town but it was to become its greatest.

The Grimsby Ice Company was originally founded in 1863 by local fishing smack owners to import ice from Norway. A peak was reached in 1900 with the importation of 86,685 tons of ice, but the supply was unreliable and prices rose with growing demand.

The initial refrigeration plant comprised four 50rpm Pontifex horizontal double-acting ammonia compressors of 21in bore, 36in stroke. These supplied two ‘can’ ice and two ‘cell’ ice tanks.

The compressors were driven by vertical, triple-expansion steam engines having cylinders 15in x 23in x 38in diameter x 36 inches stroke. Steam was generated from six 30ft long Lancashire boilers of 7.5ft diameter. They created a working pressure of 180psi.

All working, the installed system had a total output of 300 tons of ice per day.

By 1910, the increasing demand for ice prompted the Ice Factory owners to expand production. Additional equipment was sought from the Linde British Refrigerating Co Ltd. They supplied two additional ‘can’ ice tanks having an output of 200 tons per day and two 56rpm horizontal double-acting ammonia compressors of I8.5in bore, 36in stroke.

These were driven by a vertical compound Cole, Marchant & Morley steam engine having cylinders 27in and 50ins in diameter x 36in stroke. Steam was supplied from the existing battery of six Lancashire boilers which had been supplemented with superheaters to increase efficiency.

In 1914 one of the cell tanks was converted into a can tank, followed in 1926 by the conversion of the other cell tank.

Atmospheric condensers using dock water for circulation were installed with the original plant and the surface was increased as additional compressor power was added.

Although the two plants were of a nominal capacity of 500 tons per day, by increasing the revolutions of the compressors and the addition of the last can tank, an output of 720 tons per day was achieved.

The efficiency of the steam plant was steadily improved and during the last year of its operation it was producing on average 19.5 tons of ice per ton of coal.

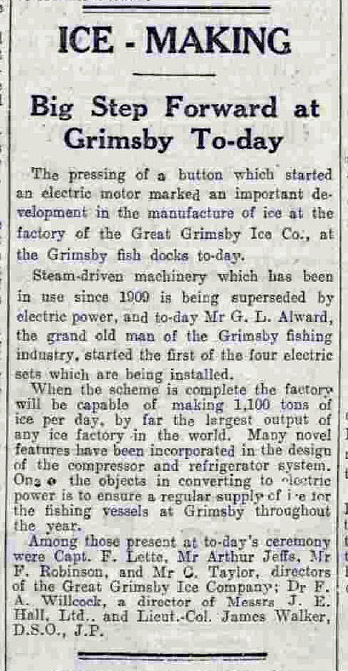

Demand continued to increase, however, and faced with the need to considerably increase output in the existing space, the decision was taken to scrap the steam plant, ammonia compressors and equipment and replace them with modern high revolution electrically driven compressors, and to modify and update the cooling surfaces in the tanks and the brine and ammonia circulation.

Order

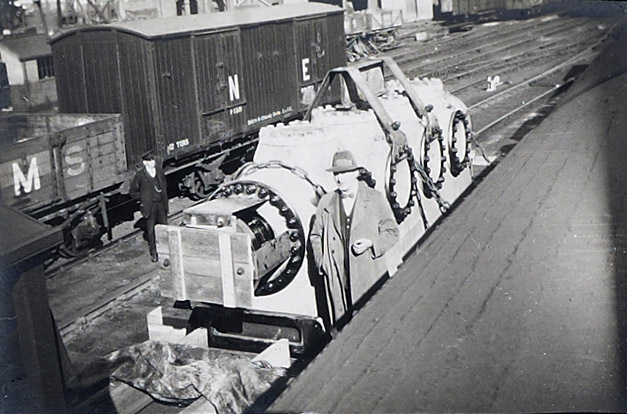

Under the direction of F A Fleming MBE, general manager of the Ice Factory, J&E Hall of Dartford, one of the iconic British refrigeration names of its time, was approached to supply the necessary refrigeration equipment.

The order and installation was the largest of its kind anywhere in the world. A welcome boost for any company but In 1931, with Britain in the grip of the Great Depression, the order was even more significant to the owners and workforce at the Dartford factory.

In Harry Miller’s 1985 history of J&E Hall Halls of Dartford, the author notes that the order announced to the employees “in a period of deepest gloom” by Hall’s boss Lord Dudley Gordon was “greeted with cheers”.

The specification for the new plant demanded an output of 1,100 tons of ice per day under ordinary working conditions, and by utilising the existing tanks without increasing the number of cans. The use of steam was to be entirely dispensed with and means to be provided for heating the thawing water without the use of electrical heaters. Much as today, this had to be achieved with equipment of the greatest efficiency.

Also, as Mr Fleming writes in a book he produced on the installation, entitled 1,100 tons Ice Making Plant, from which a large amount of information in this article is taken: “It was an essential condition that the old plant should be removed and the new plant installed without interruption of the output of ice and the supplies to the fishing fleet.

“This condition added considerably to the difficulties both of the design and of the erection of the plant,” he conceded.

“After careful consideration we decided to adopt the vertical single-acting enclosed type of compressor with forced lubrication,” he added.

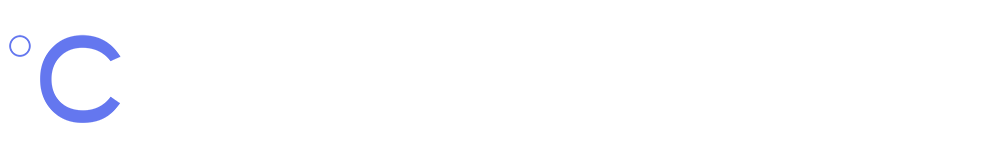

Specifically this meant four ammonia compressors, each having four cylinders operating at a speed of 250rpm. These 16.5in dia, 15in stroke machines were each directly-coupled to a 600bhp, 6,000V motor supplied in a separate contract by the Metropolitan Vickers Electrical Company of Manchester.

The compressor suction and delivery valves were of the ring plate type and the cylinders were fitted with safety heads.

The frame of each motor incorporated its direct-coupled exciter and was designed to register with and bolt up to the compressor crankcase.

The whole of the electrical control was incorporated in one automatic starting, stopping and safety device. The installation was said to be fully protected against both mechanical and electrical failures and could be instantly stopped in case of emergency.

Two large oil separators of special design were installed to guard against the possibility of oil finding its way through the condenser into the evaporator coils.

Describing the installation Mr Fleming writes “The discharge gas, before reaching the separator, is arranged to pass through a shell and tube type heat interchanger, in which the whole of the superheat is removed, thus cooling the gas and oil and ensuring its separation. The efficiency of this apparatus may be estimated from the fact that over a period of four months no new oil has been supplied, ie the oil consumption has been nil.”

It was obviously successful for in a footnote he adds “At the time of going to press, six months later, the original reserve stock of oil is still untouched in the store.”

Two sets of atmospheric condensers were employed, one which formed part of the old plant, and one which replaced an existing condenser.

Water was drawn from the docks and circulated over the coils and returned to the docks, not being recirculated over the condenser. The ammonia discharge main was common to both condensers, but stop valves were provided to shut off each of seven divisions, into which the whole of the condensing surface was divided.

The new system comprised six ice tanks and a total of 6,606 2cwt (101.6kg) cans and 3,240 2.5cwt (127kg) cans.

The ammonia evaporator coils were arranged in a trunk alongside the can space. The brine was circulated through the coil trunk, distributed evenly through the cans and then conducted back to the coil trunk. Centrifugal pumps, which were previously used to circulate the brine, were replaced by vertical spindle propellers, producing a considerable reduction in power consumption.

An absolute essential of the system design was that the output of ice should never be interrupted. Five of the six ice tanks had to have their existing evaporator coils replaced and in the case of the sixth tank the coils, which were relatively new, had to be withdrawn for alteration.

The shell and tube heat exchanger on the roof removed superheat from the gas. This recovered heat was then used to release the ice from the moulds.

After leaving the heat exchanger, the ammonia refrigerant passed through two oil separators and two sets of atmospheric condensers cooled by circulated dock water.

Water was taken from local bore holes and frozen in moulds in the ice tanks. The evaporator coils were arranged in trunks along the side of each tank.

Tests

The Initial run-tests were carried out on just one compressor but these were not without their problems. When electricity was first applied the compressor ran backwards and the engineers from Metropolitan Vickers were called in to reverse the electrical connections. It then ran successfully for a few hours before a knocking noise was heard. The compressor was shut down and investigations found a seized gudgeon pin in the no3 piston. A new piston, gudgeon, connecting rod and bottom end bearings were delivered from Dartford and the compressor was back up and running within 24 hours.

According to F A Fleming, one tank was placed at J&E Hall’s disposal in the autumn of 1931. By December 1931 the second tank which had been handed over after the first was completed, was also ready and coupled up to the first compressor.

He reported in his book 1,100 tons ice making plant: “This enabled us to commence dismantling the 200 ton Linde compressor to provide room for the remaining three new compressors, the first of which was set to work simultaneously with the third ice tank early in March 1932, the next, with the fourth ice tank shortly after, and the last on July 4th, 1932. The last ice tank is just about to be put into commission and we expect to complete the alterations by the end of July.”

Divesting of the boiler house and coal handling space freed 4,800ft2 of space and losing the old engine room for the Pontifex compressors freed a further 3,600ft².

The new condensers, together with the oil separators and the shell and tube gas cooler which heated the thawing water, were reported to occupy little more space than was originally occupied by the existing condensers.

Inauguration

On Wednesday, December 16, 1931, the Grimsby Daily Telegraph ran the headline Mammoth Ice Factory Inaugurated, noting that the modernised factory “will be capable of producing 1,100tons of ice per day – by far the largest output of any ice factory in the world.”

A further compressor room was added in the early 1950s. This contained one compressor – another four cylinder J&E Hall model – which also survives, but about which little is known. It was at this time that a further well was sunk on the site and a seventh ice tank added.

Demise

The eventual decline of the Grimsby fishing industry led to a turndown in demand and changes in ice production technology led to down-scaling in 1976. The factory finally closed its doors in 1990.

The Ice Factory is now in a state of near dereliction. The current owners, Associated British Ports, inherited the building when it was already in a poor state. Nothing has previously been done with this listed building due to the cost and enormity of the task of repair, North East Lincolnshire Council’s concentration on other priorities, the lack of any obvious use for the building and the demands of commerce and security requirements for the docks.

The Grimsby Ice Factory is on English Heritage’s “At Risk” register, and was named one of the Top Ten Endangered Buildings for 2010 by the Victorian Society.

The Great Grimsby Ice Factory Trust (GGIFT) was formed in July 2010, following public meetings organised by the Grimsby and Cleethorpes Civic Society, by a diverse group of local people who are united by the desire to save the Ice Factory and find a sustainable new use for the building.

The Great Grimsby Ice Factory Trust (GGIFT) was formed in July 2010, following public meetings organised by the Grimsby and Cleethorpes Civic Society, by a diverse group of local people who are united by the desire to save the Ice Factory and find a sustainable new use for the building.

A survey of the building commissioned by North East Lincolnshire Council and published in 2011 declared that it could cost up to £5m to preserve the historic building and its unique, 80- year-old refrigeration equipment.

It did, however, report: “Overall this report finds that the Ice Factory buildings have a generally high significance and the ice making machinery an exceptional significance, on the basis that the Ice Factory is a very rare building type to survive, is substantially complete, and contains Britain’s last surviving examples of in-situ early to mid 20th century refrigeration equipment. The four J & E Hall ammonia compressors installed in the Compressor House in 1931 are probably the oldest, and the largest, to survive in the UK and possibly also Europe. They are considered to be of international interest”

Undeterred by the report GGIFT raised the £20,000 for an options appraisal, the first step towards applying for development grants and funding. Their efforts soon attracted the interest of the Prince’s Regeneration Trust, who saw the potential the Ice Factory has, as a catalyst for regeneration in the East Marsh area.

In February 2012 the Prince’s Foundation for Building Community organised a Planning Workshop in Grimsby, which looked at connectivity between the docks and the town, and the potential for improvements in the wider East Marsh area.

A number of other national organisations have lent their support to GGIFT, including the Architectural Heritage Fund, English Heritage, The Victorian Society, SAVEBritain’s Heritage and the Council for British Archaeology. The Trust is also supported by the Enrolled Freemen of Grimsby, Freshney Place Shopping Centre, Grimsby Institute, The East Marsh Community Trust, Lincolnshire Heritage, The Society for Lincolnshire History and Archaeology, The Institute of Refrigeration and Civic Voice.

At the end of last year, GGIFT made a submission to the Heritage Lottery Fund for Major Batch funding for the next stage in the redevelopment of the Ice Factory. A decision is expected in April.

As is customary, the Cooling Post would like to acknowledge a number of people without whom this article would not have been possible.

Firstly to Rex Critchlow, one of North Lincolnshire’s leading architects and the man responsible for applying to English Heritage to have the Grimsby Ice Factory listed. Without him all of this would already be so much scrap metal. Sadly, he died four years ago but I would intrigued to learn how he, an architect, had the foresight to recognise the historic significance of the refrigeration equipment within this building. A fitting memorial to the man was carried by the Grimsby Telegraph

Secondly, to the unknown individual at J&E Hall who recognised the historic significance of this material and entrusted it to the safe-keeping of the National Archives.

And thirdly, to the good people at GGIFT who have battled against the odds, scepticism and a fair amount of local opposition to bring us to a situation today where the building has at least an evens chance of being preserved. They deserve and would welcome any support you could give. You can view their website here: ggift.co.uk

Part 2, more details on the installation, now online here